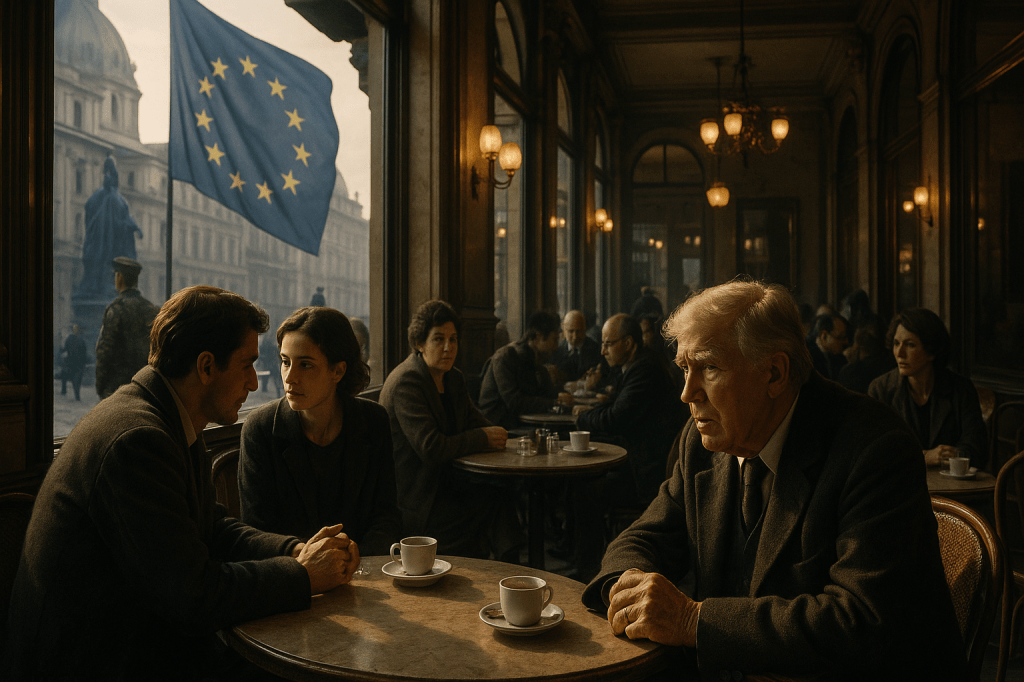

“Wherever coffee is served with a certain elegance, there exists an idea of Europe.”

— George Steiner

Eighty years after the surrender of Nazi Germany, Europe finds itself again in a moment of reckoning. What was once celebrated as the “end of history” now seems like a fragile interlude between disasters. In cafes from Lisbon to Krakow, where democracy once felt mundane, the sound of distant tanks and the shadow of authoritarian ideas remind us that the project of Europe—democratic, social, pluralistic—is once again under siege.

This isn’t merely a geopolitical crisis. It is an existential one. Across the continent, democratic institutions are eroding from within, while external threats reawaken the ghosts of territorial conquest. As war returns to Europe’s soil, populist movements rise at its heart. The idea of Europe—as a civilizational promise grounded in peace, rule of law, and shared identity—is faltering.

What does it mean to be European today? Is Europe still a community of values, or has it become just a geographic convenience, fragmented by economic asymmetries, cultural anxieties, and mutual suspicion? This article revisits Europe’s civilizational arc—not nostalgically, but critically—to ask what remains of its moral project, and whether it can still be saved.

The idea of Europe predates the continent’s political geography. It was once synonymous with Christendom, a spiritual and territorial unity under Rome, expanded through crusade and conversion. From Charlemagne to the Habsburgs, the continent was held together not by borders but by the invisible bonds of faith and fealty. The Reformation and the Peace of Westphalia (1648) fractured that order, giving way to a continent of sovereign states and shifting alliances. Europe became a chessboard of power rather than a cathedral of unity.

The Enlightenment promised a new coherence—rooted not in religion, but in reason and rights. Philosophers like Kant imagined a perpetual peace built on republican values and international cooperation. That vision persisted, in varying forms, through the French Revolution, the liberal revolutions of 1848, and the postwar reconstruction of 1945. Each epoch, despite its violence, contributed to the forging of a common civic ideal: that Europe might someday become more than the sum of its parts.

Yet that promise has always been vulnerable. The 2008 financial crisis exposed deep fault lines—not just between creditors and debtors, but between northern and southern Europe, elites and citizens, cosmopolitans and rooted locals. Resentment festered, fueled by austerity, unemployment, and the perception that the EU served markets better than people. That resentment was neither ephemeral nor irrational: it gave voice to a growing skepticism toward the liberal consensus.

What followed was not a rejection of Europe per se, but a rejection of the way Europe was being built. Populist parties from Hungary to Italy, from Poland to the Netherlands, capitalized on this mood. They channeled anger not only toward Brussels, but toward migration, multiculturalism, and the erosion of traditional identities. The continent’s political grammar shifted: sovereignty, security, and cultural preservation became dominant themes.

Then came war. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 reintroduced tanks, trenches, and terror to the European landscape. For decades, Europe imagined itself a post-war space; now it funds weaponry, debates conscription, and reconsiders strategic autonomy. NATO expanded, Germany rearmed, and Finland and Sweden abandoned neutrality.

But even as Europe responded with a show of unity, the war exposed its moral confusion. Is Europe defending democracy, or merely its own borders? Can it be the bastion of human rights while accommodating regimes that challenge them from within? The line between defending liberal order and becoming fortress Europe has grown perilously thin.

The real threat, however, may not come from Moscow—but from within the Union. Illiberal democracies, judicial capture, media manipulation, and academic censorship are no longer the exception. They are part of the European reality. From Viktor Orbán’s Hungary to Giorgia Meloni’s Italy, a new political common sense is emerging—one that prizes identity over pluralism, tradition over rights, and national will over supranational law.

Worse still, these regimes often invoke “European values” to justify their illiberalism. They claim to protect Europe’s soul from decay, even as they dismantle the institutions that sustain it. Meanwhile, segments of the radical left, in their postcolonial fervor, challenge the very legitimacy of European universalism, framing it as a colonial imposition rather than an emancipatory project.

Europe thus finds itself trapped between two extremes: a reactionary nostalgia that weaponizes heritage, and a cynical relativism that undermines shared norms. Both threaten the fragile architecture of rights, law, and reason that defines the liberal European tradition.

To speak of the “death” of the idea of Europe is not to predict collapse, but to warn of erosion. Projects like Europe do not end with an explosion; they fade into irrelevance. When citizens no longer feel represented, when borders become walls instead of bridges, and when pluralism is viewed as weakness, the soul of Europe is already in retreat.

And yet, there is still time. The idea of Europe is not dead—but it is endangered. Its survival depends not only on treaties or budgets, but on imagination, courage, and recommitment. We must recover the sense that Europe is not merely a market or a currency, but a moral and political space where differences coexist under the rule of law. A space where history is neither erased nor weaponized.

If the war taught us anything, it is that peace cannot be taken for granted. Nor can Europe.

Not anymore.

Deixe um comentário